NASA Project Mercury - Scott Carpenter and Aurora 7

This page is part of a series on America's first manned space program, Project Mercury. Links to all the hubs in this series can be found at the NASA Project Mercury Overview.

With John Glenn's successful flight in February, 1962, Project Mercury had met all of its original objectives. An American had orbited the earth and returned safely, demonstrating that astronauts could function comfortably in weightlessness for extended periods.

With the reliability of the Mercury spacecraft proven, NASA felt that astronauts could now spend less time monitoring and evaluating spacecraft systems while in orbit, and engage in other important activities. On the next flight, the astronaut's agenda would include a greater number of scientific experiments and observations.

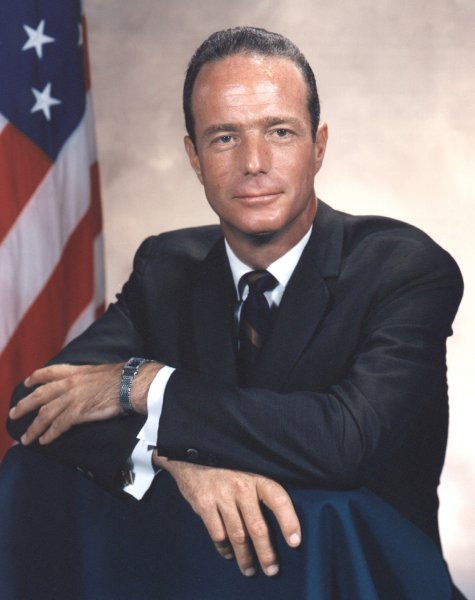

Carpenter Selected As Pilot

Donald (Deke) Slayton was the scheduled pilot for this flight. Slayton had been recently grounded by NASA, however, due to idiopathic atrial fibrillation, or an irregular heart beat.

Wally Schirra was the backup pilot, but NASA decided to deviate from the schedule and give the flight to Scott Carpenter instead. Carpenter had logged more time in the Mercury flight simulators. He'd also been backup pilot for the previous flight, which had many similarities to NASA's plan for this flight.

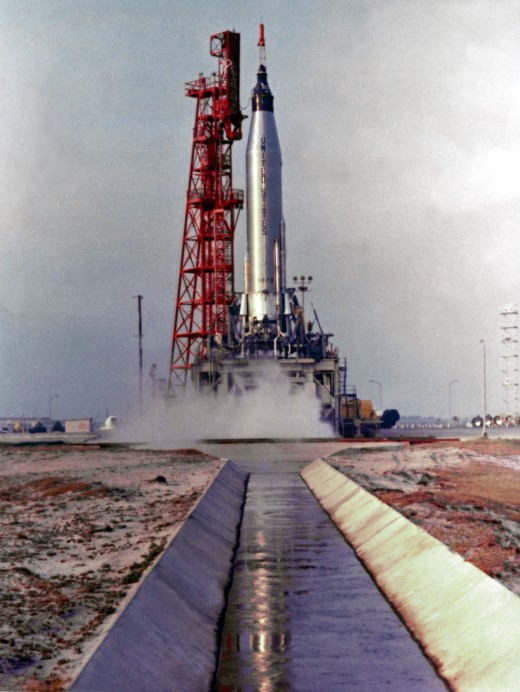

Launch of Aurora 7

Launch was at 7:45:16 EST on May 24, 1962, from Cape Canaveral, Florida. The Atlas launch vehicle and the Mercury spacecraft, which Carpenter named Aurora 7, were nearly identical to those used on the previous flight by John Glenn.

Carpenter's mission, officially named Mercury-Atlas 7, was like Glenn's in other ways. Both orbited the earth three times, with each orbit lasting just over 88 minutes. Perigee (lowest altitude) of each astronaut's orbit was approximately 100 miles, while Carpenter's apogee (highest altitude) of 166.8 miles was about 5 miles higher than Glenn's.

Lasting just over 04 hours and 56 minutes, Carpenter's mission was less than a minute longer than Glenn's. Carpenter travelled a total of 76,021 miles, just 342 miles more than John Glenn.

Science In Space

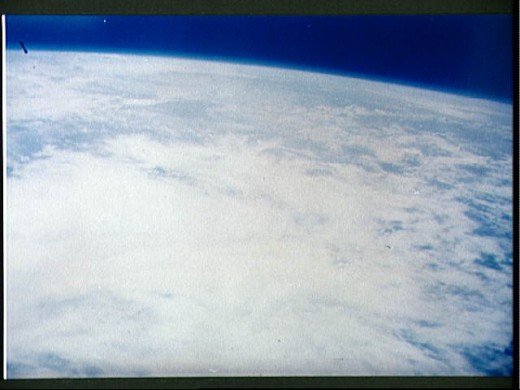

Carpenter's in-flight activities included a study of liquids in weightlessness, and an investigation of the bright band of light seen above earth's horizon by John Glenn.

Carpenter determined that this light was actually airglow, an atmospheric phenomenon that creates a small amount of luminescence in the sky even on dark nights. He measured the brightness, wavelength and height of this phenomenon.

Not all experiments were successful. An attempt to measure atmospheric drag at the edge of space failed when a balloon tethered behind the spacecraft did not fully inflate. Carpenter's attempts to see flares fired from the ground were thwarted by clouds, and he ran out of time before completing a series of earth photographs for the U.S. Weather Bureau.

A series of photographs for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was also not completed. MIT was developing the navigation system for Project Apollo, and hoped these photos would help determine if earth's horizon could be used as a navigational reference on lunar missions.

Excessive Fuel Consumption

Early in the flight, Carpenter used up a great deal of fuel positioning his spacecraft to better appreciate the view from space. To conserve remaining fuel, he was instructed to let his spacecraft drift freely for more than an hour.

Later in the mission, Carpenter saw the mysterious particles that John Glenn had described as "fireflies", and he varied from the flight plan to investigate and photograph them. He could see they were not truly luminescent, but were merely reflecting sunlight. The particles were flakes of frost that had formed on the outside of the spacecraft. Carpenter had solved this mystery, but at the cost of still more precious fuel.

To learn more about retrorockets and other aspects of the Mercury capsule, see NASA Project Mercury - Spacecraft

As the time to fire the retrorockets approached, Carpenter felt that the automatic controls had not positioned the capsule correctly for retrofire. The orientation of the spacecraft was critical during retrofire and re-entry. A spacecraft entering the atmosphere at the wrong angle could burn up.

Carpenter took control of the spacecraft using a system known as fly-by-wire control. Unfortunately, a second set of manual controls had been accidentally left on as well, causing the maneuvers to use more fuel than they should have.

Carpenter soon saw and corrected the problem, but he could no longer be certain that enough fuel remained to stabilize the capsule during re-entry. In addition, unknown to Carpenter, a malfunction in the navigation system meant the capsule was still misaligned, even after the manual adjustments.

Late Retrofire

Investigating John Glenn's fireflies and manually orienting the spacecraft put Carpenter behind schedule. He needed to quickly complete a series of tasks to prepare for retrofire. Controllers on the ground became concerned, believing Carpenter was sounding tired and confused, though they recognized he may simply have been preoccupied with completing his tasks.

When the retrorockets failed to fire automatically at the scheduled time, it took Carpenter several seconds to manually fire them. When they finally fired, they produced slightly less thrust than expected. These retrofire problems, combined with the incorrect orientation of the spacecraft, would cause Carpenter to splashdown hundreds of miles off-target.

In-flight recording of Scott Carpenter during re-entry:

Re-entry

The angle of Aurora 7 during re-entry was more shallow than it should have been, meaning the spacecraft might experience higher temperatures than expected. Fortunately, the heatshield provided Carpenter with adequate protection throughout.

His fuel was soon exhausted, however, leaving him with no way to stabilize the spacecraft as it fell through the atmosphere. As the oscillations of the spacecraft increased, Carpenter chose to release the drogue parachute ahead of schedule, which helped stabilized the craft. The main parachute opened shortly after that, carrying Aurora 7 to a safe splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean.

Scott Carpenter, Astronaut/Aquanaut

Mercury-Atlas 7 was Scott Carpenter's only space flight, although he continued to work for NASA in an executive position until he retired from NASA in 1967. In 1965, on leave from NASA, Carpenter became the first human to explore both outer space and the depths of the ocean when he spent 30 days living on the ocean floor as part of the US Navy's SEALAB II project.

Video - US Navy's Sealab II (3 Parts):

Recovery

He had no way of knowing it, but Carpenter had missed the target splashdown area by 250 miles. Thanks to tracking data, NASA was able to calculate where the spacecraft would be, but it would be at least an hour before recovery forces could reach that area.

Because the communications equipment on Aurora 7 operated by line-of-sight, Carpenter was unable to communicate with NASA or any recovery vessel. NASA, and the American public watching on TV, had no way of knowing the status of Carpenter and his spacecraft.

Carpenter was spotted by rescue aircraft roughly 45 minutes later. Frogmen entered the water to check on Carpenter's condition, and to place a flotation collar around Aurora 7. It was another two hours before a rescue helicopter arrived to carry Carpenter to the recovery vessel, the USS Intrepid. Aurora 7 was pulled from the water several hours later by the USS John R. Pierce.

Conclusion

The mission had not been flawless, but the Mercury spacecraft performed well enough that NASA felt it could move ahead with plans for longer missions. The capacity for man and machine to meet the increased demands of these longer missions was still unknown, however, so the focus would return to observation and evaluation of the spacecraft and astronaut for the next flight.

References

In addition to the sources listed on the Project Mercury - Overview page, information for this hub came from the following original source document:

- Manned Spacecraft Center, Results of the Second U.S. Manned Orbital Space Flight - May 24, 1962, NASA, 1962